How do racing oils differ from everyday motor oils? You might think all racing oils are synthetics, but they are not. Some use conventional mineral base oils, others use PAO and ester synthetics, and some are a blend of conventional and synthetic oils. Some racing oil suppliers refine their own oil while others are blenders who buy base stocks from other oil companies and mix in their own additive package. It doesn’t really matter which way a racing oil is created as long as it meets the criteria for which it was designed.

How do racing oils differ from everyday motor oils? You might think all racing oils are synthetics, but they are not. Some use conventional mineral base oils, others use PAO and ester synthetics, and some are a blend of conventional and synthetic oils. Some racing oil suppliers refine their own oil while others are blenders who buy base stocks from other oil companies and mix in their own additive package. It doesn’t really matter which way a racing oil is created as long as it meets the criteria for which it was designed.

Racing oils are formulated for hard use, high temperature operation. This requires a high quality base stock with an additive package that provides superior wear resistance and oxidation resistance compared to an everyday motor oil. Base oils make up 70% to 90% of the liquid that’s in a bottle of oil. The rest is various additives. A high quality base oil usually requires fewer additives to achieve good performance, while less quality oils need a better additive package. The bottom line is that two different racing oils formulated using different base stocks and additive packages can often meet the same performance criteria.

When choosing a racing oil, therefore, comparing apples to apples can be difficult because of the different base stocks and additives that are used. Most oil companies will only hint at what’s in their product, preferring to keep their exact formula a proprietary secret. They may make certain claims as to how the oil performs or how much anti-wear additive it contains, but trying to compare one motor oil directly to another can be very confusing. Motor oils with the same viscosity rating can have very different additive packages and very different performance characteristics. So the best advice we can offer when it comes to choosing a particular brand of motor oil is to go with a brand that has a good reputation with the racing community. It doesn’t matter if the product is made by a big oil company with a big promotional ad budget or blended by a small supplier who relies on word-of-mouth advertising.

That said, let’s take a closer look at what goes into a racing oil and how that may affect the way you choose to build an engine.

All About That Base

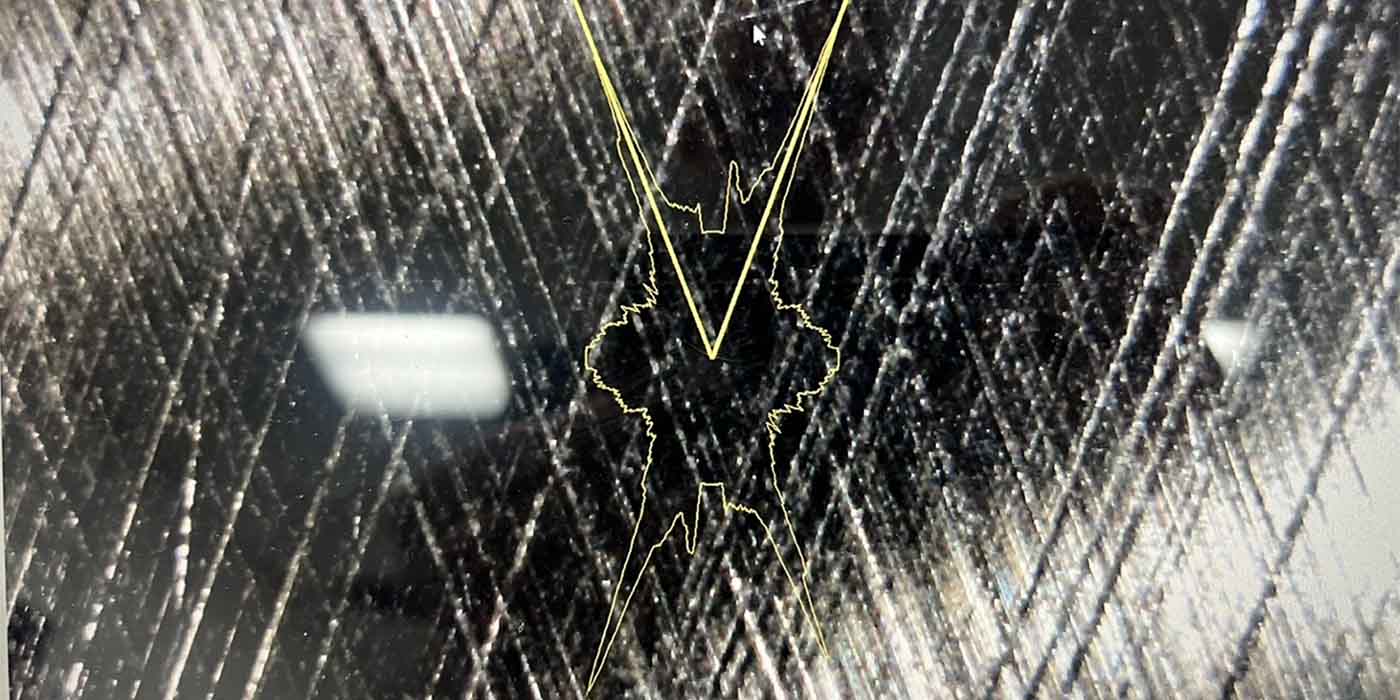

Base oils are rated according to their “Viscosity Index” (VI) or pour point, how many “saturates” (paraffin and naphthenes) they contain, sulfur content, volatility, flash point, oxidation stability and other factors. Petroleum engineers have developed test procedures and a rating system for grading various base stocks.

• Group I oils are the easiest to refine and least expensive lubricants. They also contain lower levels of saturates (less than 90), higher levels of sulfur (over 500 ppm) and usually have a viscosity index rating of less than 100. Group I mineral oils have long been used in straight weight and multi-viscosity everyday motor oils, and are often blended with Group II or III oils in some multi-viscosity oils. But Group I base oils are generally not used in racing oils.

• Group II base oils are higher quality lubricants that are commonly used in today’s multi-viscosity oils. They contain a higher percentage of saturates (greater than 90), lower levels of sulfur (less than 500 ppm), and have a viscosity index rating over 100.

• Group III base oils have a viscosity index rating usually over 120, and include many synthetic oils.

• Group IV base oils are pure PAO synthetics and are the highest quality generally used in automotive applications.

Which group a base oil ends up in depends on how it was refined or made, and how it performs. Mineral base oils are refined from crude oil (paraffinic, naphthenic and aromatic) while synthetic oils undergo additional refining and may be made from crude oil or natural gas. Synthetic oils fall into several subcategories: PAOs (polyalphaoefin), diesters, polyol esters and PAGs (polyalkylene glycols).

This is a lot of chemistry you really don’t need to know to choose a racing oil. But it’s helpful to understand what some of these terms mean and how marketing people tend to misuse them in promoting various high performance lubricants.

The general consensus is that synthetic oil is better than conventional mineral oil. Most synthetic oils do have inherent advantages over conventional oils because synthetic oils undergo additional refining, distillation and purification that results in a very high quality and consistent base stock. Synthetic oils generally pour more easily at lower temperatures, resist oxidation better at higher temperatures, stay cleaner longer (extended drain intervals) and superior lubrication and wear protection. One oil supplier says the molecules in synthetic oils are more consistent in size. This allows a synthetic oil to provide a higher film strength. Translated, this means although a synthetic oil is often thinner than a conventional mineral oil, it clings better to bearing surfaces under load.

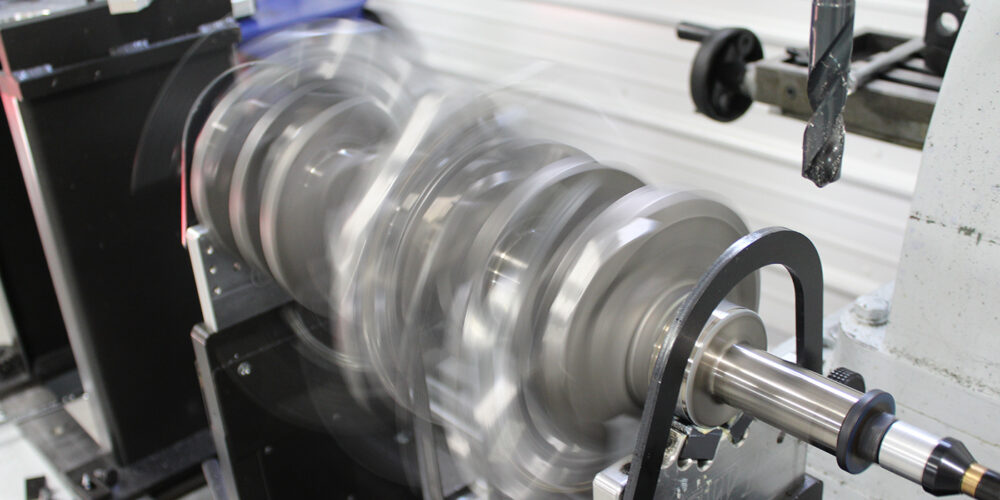

Synthetic oils also have lower volatility, which reduces evaporation losses when the oil is hot. Synthetic oil is also more sheer stable, which means its viscosity characteristics are more predictable and consistent, and undergo less change over time than a conventional mineral oil. Some synthetic oils also provide better air release, reducing the risk of aeration and bubbles being trapped in the oil when it is being whipped into foam by a spinning crankshaft.

High-quality conventional mineral oils can perform well in many racing applications with the right additive package, but for the most demanding applications many oil experts say a full synthetic will usually provide the best protection and performance.

Oil is relatively cheap, even the most expensive full synthetic racing oils when you compare the cost of the oil to all of the machine work and parts that have gone into a high performance engine. Why scrimp on oil quality and risk an engine failure if a premium quality racing oil can provide extra protection?

The Antidote to Wear

One of the key components in any racing oil is anti-wear additive. Typically this includes ZDDP (zinc dialkyl dithiophosphate) as well as other ingredients such as moly. ZDDP is a mixture of zinc and phosphorus, although many people simply refer to it as “zinc”. The exact proportions of zinc and phosphorus in ZDDP can vary somewhat but generally there is slightly more phosphorus than zinc. Under extreme pressure, these compounds provide a protective barrier that prevents metal-to-metal contact and wear.

Everyday motor oils for passenger car and light truck applications that meet current API (American Petroleum Institute) “SN” specifications and/or ILSAC GF-5 specifications contain reduced levels of ZDDP (less than 800 PPM). Phosphorus is great stuff for preventing wear, but it can also contaminate catalytic converters and oxygen sensors, reducing service life – especially if the engine is burning oil due to worn valve guide seals or piston rings. The amount of ZDDP in current motor oils was reduced from earlier levels of 1200 PPM because most late model engines have roller cams or overhead cams. Reduced friction in the valvetrain means these engines don’t need as much ZDDP for wear protection. But that’s NOT the case with performance engines or older engines with flat tappet cams. They need higher levels of anti-wear protection.

Most people assume that one of the hallmarks of a racing oil is that it contains at least 1500 PPM of ZDDP, or even more (some contain as much as 2000 PPM of ZDDP). That’s generally true, but there are performance lubricants on the market that contain as little as 1100 PPM of ZDDP thanks to the higher quality base oils in the product and other additives (such as moly).

The exact amount of ZDDP in a racing oil doesn’t matter, nor does more always mean better as long as there is enough to protect the valvetrain components against wear. Some engines need more, some can get by with less. Extremely high RPMs and extremely stiff valve springs can place tremendous loads on the cam and lifters, so foe these applications a racing oil that contains extra ZDDP or other anti-wear additives is usually a must to prevent cam or valvetrain failure.

Taking it to the Streets

Street performance oils are a subcategory within racing oils that are formulated for the typical vintage muscle car or street/strip machine. Some of these oils are not API-rated, although they usually meet all of the other performance criteria for a modern motor oil. The main difference is that they contain 1200 PPM or more ZDDP to protect flat tappet cams and lifters against premature wear. Since most of these vehicles are not equipped with oxygen sensors or catalytic converters, phosphorus contamination is not an issue. Such products are usually NOT recommended for late model vehicles that have electronic engine controls (O2 sensors) and catalytic converters.

For more demanding racing applications, specially formulated racing oils with the highest quality synthetic base stocks may be required to provide the utmost protection and lubrication. Some racing oils are formulated for engines that are running alcohol, or for blown, turbocharged or nitrous applications. The best advice here is to follow the application recommendations of the oil supplier. They know their individual additive packages and formulations and can help you choose a product that is right for the application.

Viscosity Confusion

Most late-model passenger car and light truck engines are factory-filled with 5W-20 or 5W-30 multi-viscosity oil, with some European makes specifying 0W-40 or even 0W-20 for Japanese hybrids like the Toyota Prius. Thinner oils make cold starting easier and improve fuel economy. Thinner oils also flow more quickly following a cold-start to speed lubrication to the bearings, cam and upper valvetrain. For older pushrod engines, 10W-30 is still the most popular viscosity. But for racing applications, the viscosity you choose can vary depending on engine bearing clearances, ambient temperatures, engine RPMs and customer preferences.

Racing oil viscosities run the gambit from newly introduced 0W-50 and 0W-60 multi-viscosity synthetic oils to 0W-30, 0W-40, 5W-20, 5W-30, 5W-40, 10W-30, 10W-40, 15W-40, 15W-50 and 20W-50 multi-viscosity oils, to various straight weight oils including 30, 40, 50 and 70.

Each oil is formulated for a particular niche, but the oil companies usually won’t tell you which oil they recommend. They leave that up to the engine builder and the end user to decide.

Traditional old school engine builders and racers like looser bearing clearances, lots of oil pressure and a relatively thick oil such as 15W-40, 15W-50 or a straight 40 or 50 weight oil in the crankcase. A heavier viscosity oil helps cushion the bearings and won’t drain off as quickly as a thinner viscosity oil if the engine loses oil pressure momentarily.

Others say they can gain additional horsepower running tighter bearing clearances, less oil pressure and using a lower viscosity racing oil such as a 0W-20, 0W-30 or 5W-20. Thinner oils require tighter bearing clearances to maintain oil pressure, but they also reduce friction to free up more horsepower. What’s more, they can reduce the load on the oil pump which also frees up more power.

One of the most common misconceptions with thinner multi-viscosity oils is that might be too thin to provide adequate lubrication in a high performance engine at high temperature. The numbers on a multi-viscosity rating tell a different story. The first number is the viscosity when the engine is cold. The lower the number, the thinner the oil and the easier it flows. The second number is the viscosity when the oil reaches operating temperature. Consequently, once the oil is hot, a 0W-40 oil flows and lubricates the same as a straight 40 weight oil. This transformation occurs thanks to the rubber-like “viscosity improvers” that are blended with the base oil to give it its multi-faceted personality.

For higher temperature applications (such as endurance racing in hot climates), a heavier multi-viscosity oil is usually recommended (something like a 15W-50 oil). Recently, however, several oil companies have introduced 0W-50 and 0W-60 multi-viscosity racing oils for rally racing and off-road racing. The broader viscosity provides good cold lubrication for overhead cams and turbocharger shaft bearings, while the higher hot viscosity rating keeps everything well lubed at peak operating temperatures.

For a really demanding application such as Top Fuel drag racing, a heavy straight weight oil (usually 70) is required because of the extreme loads on the bearings and the fuel blowby that ends up in the crankcase. And the oil is usually so diluted after each run that it usually has to be changed.

How often should racing oil be changed? It depends on the application and how far the end user wants to push his oil. If the oil looks dirty and/or smells bad, it needs to be changed. Dirt track racing and off-road racing are very dirty environments, so changing after every weekend of racing is a common practice. A drag racer, on the other hand, might go all season on the same batch of oil unless he sees a lot of fuel dilution in the crankcase or oil discoloration.

The bottom line is there is no pat answer as to how often racing oil should be changed. Oil life depends on the quality of the oil, the additives in the oil, how hot the oil gets and how much contamination ends up in the crankcase. Obviously, if an engine has experienced a major bearing, piston or rod failure, the old oil has to go and everything has to be thoroughly cleaned to remove any debris that could cause problems later on. This includes flushing out all the oil galleys, external oil lines, oil cooler and/or reserve tank.